People

‘I Was So Afraid for Way Too Long’: Painter Jonas Wood on How Going It Alone Helped Him Survive His Immense Market Success

Wood's advice for young artists trying to make a living? Don't take money from dealers.

Wood's advice for young artists trying to make a living? Don't take money from dealers.

Pac Pobric

Jonas Wood is not shy. He won’t hold back, takes aim when he fires, and doesn’t seem concerned about ruffling anyone’s feathers. He’s also busy—very, very busy—and seems to have a lot on his mind.

When artnet News spoke with the artist earlier this month, he was preparing for the first institutional survey of his work at the Dallas Museum of Art, which opened last week. The show is a real boon; although Wood has earned a solid reputation for his lush interiors, tender portraits, and vibrant still lifes, which he has shown in dozens of commercial gallery exhibitions, museum support has largely eluded him until now. Not that he has much time to bask in his success. In April, Gagosian will present new works by the artist in New York, which means he has to quickly shift gears and look ahead.

Yet one of his guiding principles, which he restated repeatedly throughout the interview, is how it’s essential to pause and re-calibrate. The art world moves fast. Pressures mount quickly and tastes can change on a whim. There are always more requests than there is time. So it’s absolutely necessary, he says, to carve out space to think.

As far as that’s concerned, Wood has an excess of experience, and he’s never short on advice. We spoke with the artist about how he navigates the hot market for his work, why artists shouldn’t take advances from dealers, and why he refuses to take commissions.

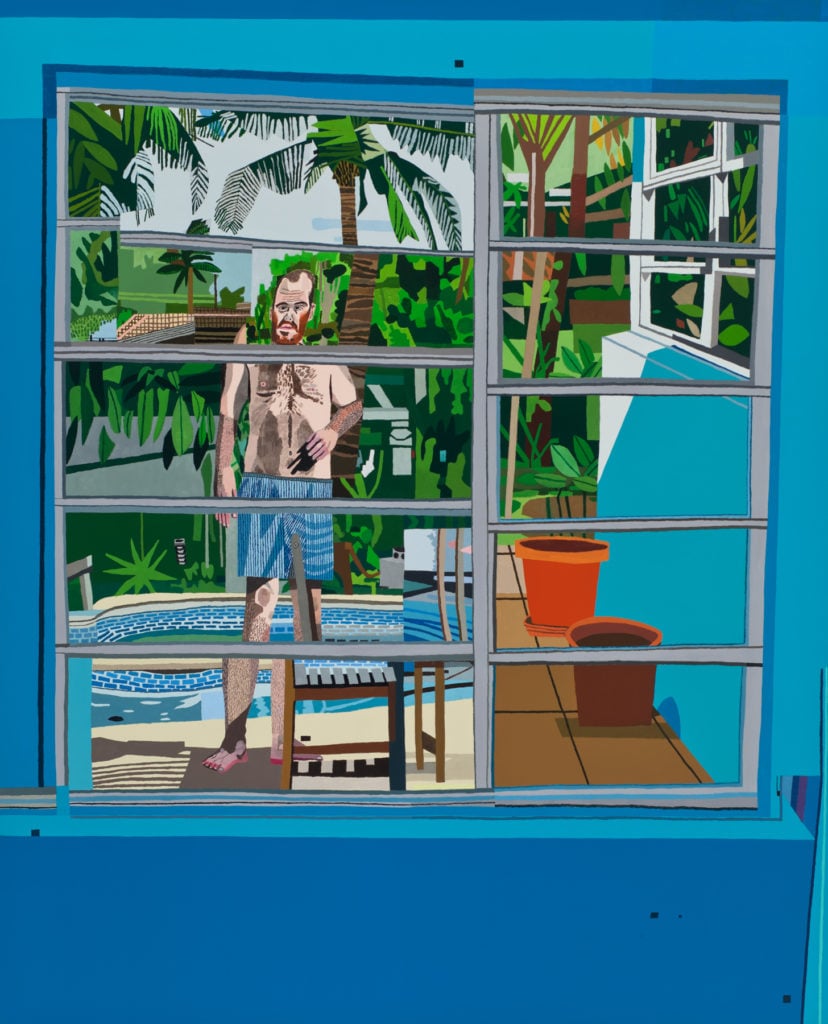

Jonas Wood, Calais Drive (2012). Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

The press release for the Dallas show mentions that your work “resonates with a wide audience.” Who would you say you paint for? Is there a particular audience you have in mind?

I think, “What artist do I want to hang my paintings next to? Where do I want to fit in?” So that’s sort of a dead audience, maybe. But I think I’m probably painting for me, to see if I can top myself or top my fears or top my friends. Not in like a ranking, but just trying to create a masterpiece, trying to make the work that transcends us, I guess. I think it happens to be that I have a broad audience right now. Maybe that’s not always the case, but the reason I paint is not for those people. I think it’s for my own mental health and for my own sort of goals as a painter, but I’m aware of the viewer.

What’s your working process like?

I work from photos. I collect photos, ones I’ve taken or I’ve appropriated or that other people have sent to me. And then I either make a collage of those things or work directly from photos. And a bunch of times, I’ll make a drawing from a found photo, a photo collage, or photo I took, and then make a painting from that drawing.

I’m not a spontaneous painter. But the spontaneity of being able to paint directly from the photo as opposed to always having to use the drawing is sort of where it deviates. And I do a variety of things in between, either making more 2D models to work from or just using the [first] 2D model.

Speaking of models, I recall you saying in another interview that you read Painting as Model by Yve-Alain Bois when you were a student, and one of the things he emphasizes is that painting is its own way of thinking.

Yeah, that’s big for me. Because as a figurative painter people say, “Your paintings are so comic book.” Or, “Your paintings are so flat,” or “The colors are strange.” And I’m like, “It’s just a painting. It’s a painting. I know it’s a painting, and therefore it doesn’t have to have the kind of rules that you think it should have.”

Everyone basically has their own set of rules when they’re limiting themselves and practicing within a very specific set of procedures that are still flexible—like jazz, or cooking. You sort of just have to be creative. Cooking, you have to know the temperature. And what kind of pan? What are the right ingredients?

What are some more of those other irrelevant questions people ask you?

Okay, so I get asked this question a lot. “How long does it take you to make something?” Or, “How many paintings do you make in a year?” And I don’t really know, because those are two things that I choose to not think about because I don’t think it’s relevant—especially because I work on a lot of paintings at once. So it’s really hard to determine the amount of time I actually spend on them.

And the other thing is, “How many paintings do you sell a year?” I think a lot of people think it’s some formula that I’ve cracked to get this far. And I didn’t want to know how many paintings I made because it doesn’t really matter. I think it matters how many paintings you release, and that makes you edit so you only release your best work. And you just sort of hold tight and you save things.

Jonas Wood, Jungle Kitchen (2017). Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

I’m sure a lot of young artists are thinking about this. What advice would you give? How do you navigate the tremendous pressures of having to produce for the market, or for an art fair? How do you stay sane and continue to be productive and happy with your work?

Okay. That’s a good question, and I can answer it. When I was younger and starting out, I got advice from Mark Grotjahn. It was 2007 when I met him, so he was huge in LA. He already had an office, he already had somebody working for him. He had people helping him out. Mark’s one of my best friends. And I got advice from Laura Owens. I worked with Laura Owens. And I got this really good advice—and from other people too—which was just, if you want to separate yourself from the noise, you’ve got to create some distance.

You’ve got to hire [somebody to run] an office. You’ve got to protect yourself. Because the nature of a gallery is to ask you for work to sell. And if you’re popular, or if you’re doing well, they’re never going to be like, “Do you know what? You should take a break. We don’t want to sell your work for a year.” Unless they’re trying to do some sort of crazy market scam where they’re going to jack it all up or whatever.

I get there are some dealers who are giving you good advice. But inherently, they’re just going to want to sell, and they’re hoping that you’re the one who’s going to stop them. But when you’re younger, you’re very afraid that the dealers hold all the power. They can cut you off. They’re not going to sell your work anymore. So I got this advice: set up an office. I was getting requests and stuff, but at least it was getting filtered through my people. And then I was talking with a person that I wanted to talk to, on my time, and start figuring out what I wanted to do. And I knew I was selling the work more and more, and I was more aware that, “Hey, this is a collaboration. This isn’t a dictatorship.”

This is where I’m at now, and it took years, because I was always giving extra work and not really thinking about it. Another thing was just saving my own work and not being so greedy, and being aware that, okay, $5,000 now is $5,000 now. If I sell three more paintings, yes, I’ll get a little bit more money, but it’s not like life-changing money. Maybe I should start holding onto things for myself and not selling everything.

I mean, the dealers are going to hate hearing this, but maybe they won’t. Maybe it’s good because they want an empowered artist. But they would offer to give me money to buy stretchers and buy stuff for my studio, and I didn’t really want them to buy stuff for me because I didn’t want them to know how many paintings I was making. I wouldn’t want to have to have them buy 10 stretchers and then expect for them to give them 10 paintings. I didn’t want any pressure, because I was already putting tremendous pressure on myself to paint, because I was so motivated. And obviously that’s a big reason why I’ve gotten to where I am today, because I was working really hard.

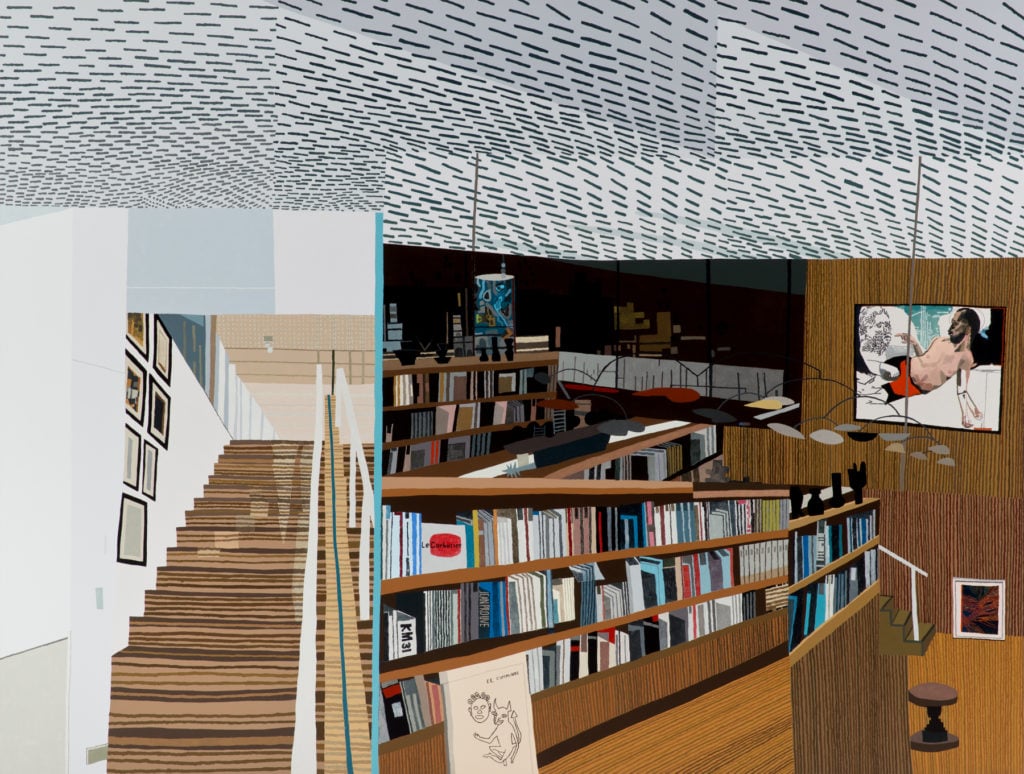

Jonas Wood, Ovitz’s Library (2013). Courtesy of the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York. Photo: Brian Forrest

So don’t take too much from art dealers?

Yeah, just not taking money from dealers. Probably the biggest thing for me is that I was like, “Hey, I’m not a commission artist. I don’t take orders like a short order cook. So I would prefer not to know what anybody wants.” If a dealer’s like, “You’ve got to make 20 of these paintings huge,” I would say, this person’s probably a fucking idiot.

It goes back to your first question. I wasn’t painting for that audience. I was painting for me, and I knew that I didn’t want to paint for the collector audience. I wanted to paint for me. I love collectors. But I knew that was a trap. Luckily all the dealers I ever worked with are really cool about it. Nobody comes at me with those type of things, and that’s really great because I know that I don’t operate that way.

So establishing that was really important for me because I was able to keep my practice open. I didn’t want to be pigeonholed right away. I showed a lot of different kinds of work, and I didn’t really cut myself off and be like, “He’s the tennis court painter.” Or, “He’s the sports portrait painter,” or, “He’s the guy who makes the still life.” I guess I’m kind of all of those things, which is better than just being one of those things

I also had the benefit of having this really crazy thing happen when I had my first show in Los Angeles. In 2006, I showed with Black Dragon Society, which doesn’t even exist anymore, and Anton Kern and Shane Campbell each offered me a show from that show. But Black Dragon Society kicked me out because I wouldn’t consign the work through them to Anton Kern. They told me that I shouldn’t interface with Anton Kern, that they would do all the talking for me and basically told me to go to my studio and paint. And I knew that was wrong. So I basically said, “No. I’ll keep showing it through your gallery, but I’m not going to consign the work through you. I’m going to show it in New York, and let’s see how it goes.” And they just sent me an email the next day and said, “We’re kicking you out of the gallery.”

And then I had no gallery in Los Angeles and that was a really big deal, because I didn’t have a hometown dealer. And I had the trust of Anton Kern and Shane Campbell. They were my only two galleries for like six years.

And then after that, you did get an LA gallery, David Kordansky.

David moved his gallery close to my studio in Los Angeles and had been courting me. And I was just like, “I don’t know if I can do this,” even though me and David are the same size, because I wanted something bigger. But it turns out working with David in 2012 was obviously one of the best things I ever did. We’re the same age, and we’re friends, and we’re growing together. So that was a big deal. All these circumstances helped lead to me to realize that I was more in control than I thought I was when I was younger.

But that’s the hardest thing when you’re really young, isn’t it? You just don’t know, and you’re afraid that—

Look, I was so afraid for way too long. I should have been less afraid in certain circumstances where I made mistakes, for sure. Because you just don’t know your worth. And even now, I’m not—I don’t see myself as other people see me. I don’t come to my studio and think, “I’m the fucking best.” That’s not really how I view myself anyway.

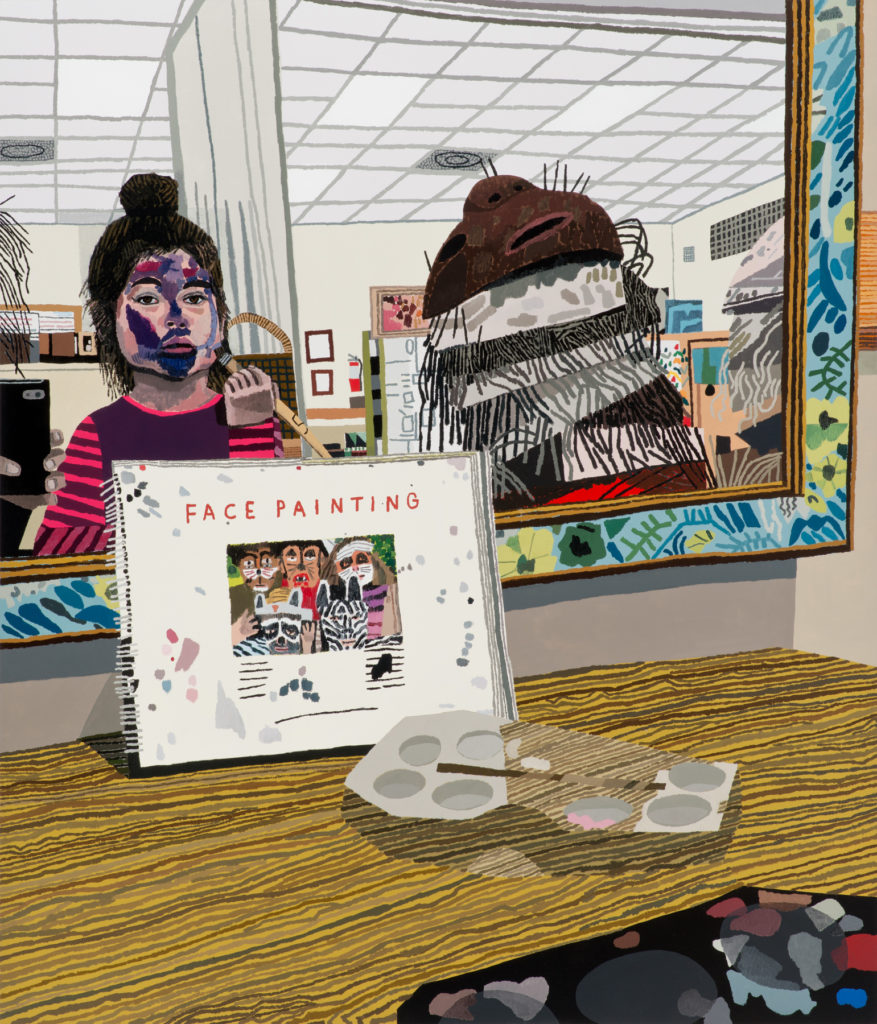

Jonas Wood, Face Painting (2014). Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

But you do see cases all the time where artists get chewed up very quickly.

Well, yeah, because I think there’s a lot of greed from both sides—from the artists too. There’s the pushy dealer, but somebody on the other side has to be saying “yes.” The dealer is pushy inherently, because how else are they going to get work? I mean, to a certain degree. But the chewed up thing is also [about] people’s misconceptions about art and art-making and painting. When you’re starting out, you’re like a micro, little, mini-baby, and you’re supposed to be having this super-long career.

And I think people lock into these modes of working, making, where they create this line of stuff. And then if they’re making all these green paintings, and then they go red, everybody’s like, “What the fuck?” I don’t know. I didn’t go to a school where there was any talk about the market.

Do you think there should be talk about the market in art school?

Well, when I was at school in 2002 at the University of Washington, my goal was to teach at a liberal arts school, have a studio on campus, have the summers off. That was probably my ideal.

But that was a different time, even in the history of the art market. You have people now finishing school with $200,000 in debt thinking they’ll be great artists, yet they have no idea how to even find a gallery. So it seems like a disservice not to talk about the art market. But what else do you think they should be talking about in art school?

Well, the mental fortitude of the whole thing. Man, it’s fucking tough because people say crazy shit about your work. You have to be super thick-skinned, and it’s hard. That’s a big part of it. I would say that you just have to take all that energy back to your studio and try to be critical in your own way and just take that criticism. Just say, “Okay, yeah, I’m going to fucking keep looking because maybe these people have a point.”

But that type of shit is tough. Dealers saying crazy shit, your friends saying crazy shit, collectors saying crazy shit, having a show where you don’t sell a bunch of stuff. That shit is tough.

Well you’re getting a lot of positive reinforcement. There’s the show in Dallas and another one now at Gagosian in New York in April.

No, it’s great. Having shows is the best thing ever. I love the theater of it. I like that people don’t know what they’re going to see when they come. I like to surprise people. And I can’t even say it’s just me. It’s me and my wife’s whole journey together as artists. I met her [ceramicist Shio Kusaka] in Seattle. I was super young. We got married, and then it coincided with us both really wanting to make art. We share staff members and a studio and kids, of course. And we appropriate each other’s work, but we actually don’t make objects together. We just have created this environment together that’s super creative and potent and fun and beautiful in our own way, together. We’re the best because we’re together.